This is kind of the post behind the post. I recently

wrote a post for the Collins ELT blog about how we updated the new edition of

Work on Your Phrasal Verbs. I was asked to make it a short, simple post for a

wide audience. You can read the post here - it summarizes the key changes in

terms of updating the phrasal verbs we included to reflect current usage (we

changed around 10% of the PV list) and also how we reworked the design to

include more space for practice activities. What the post doesn’t have

space for is explaining how we did that. So, I thought I’d write

this post-behind-the-post to give those of you who like that kind of thing a few

more of the nerdy details.

Updating the PV list was a fairly straightforward case of

checking the current corpus frequencies of the PVs in the first edition and

highlighting any that had declined in usage. I say “straightforward” – actually

checking the frequency of phrasal verbs is far from straightforward, but I’m not

going to get into that here! Then the Collins corpus team generated a list of

possible new additions based on the most high-frequency PVs that weren’t

included in the first edition. I checked the most likely candidates manually,

chose suitable options, and we worked out how to shuffle things around to fit the

new additions into the themed units to replace those we’d dropped.

When we were initially reviewing the first edition, I'd

highlighted the fact that most of the existing practice activities focused on the

basic meaning of the PVs, so a largely receptive focus. With an extra page per

unit for new activities, I suggested we could use the space to build on the

receptive/meaning-focused exercises by adding new ones that looked more at the

kind of things learners need to know to use PVs productively. For me, it was

this bit that turned out to be the most interesting part of the project as I

got to do original corpus research, then put it directly into

practice.

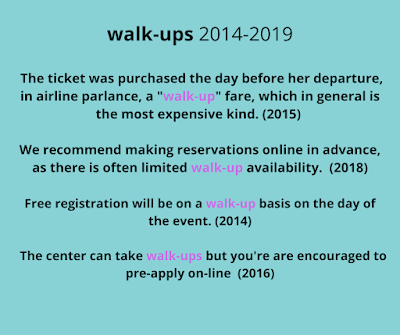

In my Collins post, I pick out four main areas we focused

on – and I also made some pretty graphics around them for an instagram post which I’m

going to unapologetically reuse!

Typical Collocations:

This is a biggie because collocations are not only

important for using language in a way that sounds natural - and produces

predictable combinations of words that readers and listeners will expect and

not ‘trip over’ – but collocations such as typical subjects and objects also

tell you a huge amount about how and where the target PV is typically used. Is

it used to talk about serious or fairly frivolous topics? Are the subjects

positive or negative things? What types of people do this thing? Is it informal

and conversational or something more likely to crop up in business

communications or journalism?

Here are some of the pages and pages of notes I made as I

researched each PV.

You can see very clearly that, in terms of typical objects,

we drop off both objects and people:

For intransitive PVs, the subjects are obviously more

interesting, like here at (not) add up:

Or here you can see what kinds of people tend to step

down:

For ditransitive verbs, like remind sb of sth,

I looked at both the direct and indirect objects:

And sometimes I noted down both subjects and objects as

worth highlighting, such as here you can see who lays off who:

But it’s not just about the nouns. There are the adverbs

too that you can see above with step down immediately/voluntarily

and not really add up. Or even the quantifiers, lay off a

lot of/hundreds of … .

I used all this mass of information to create activities

that focus specifically on collocation, like the one above, but I also tried to

include the strongest collocates of each PV throughout the unit, including them

in examples where they weren’t the main focus.

Colligation patterns:

These are the grammatical patterns that PVs tend to be

used in. At the simplest level, do you carry on read, carry on to read or carry

on reading? While scrolling through corpus lines, I often found myself noting

down following patterns, some of them simple, like a following -ing form or a

wh- clause as above. Some like at make up for were more complex,

taking in direct objects, -ing forms, wh- clauses and also a passive plus

preposition combo (be made up for in …) and a preceding phrase (more than made

up for …)

Other common preceding patterns I noted included modals

and other introductory verbs (do they have a name?), like try to, fail to,

go and …

Again, some of these made their way into explicit

exercises highlighting the patterns, often matching sentence halves, while

others just loitered in general examples, building the picture for students of

typical usage in the background.

Prepositions:

Slightly confusingly for learners, phrasal verbs often

co-occur with specific prepositions that aren’t strictly part of the phrasal

verb itself, because they’re optional or vary depending on what follows.

They’re at the niggly, detailed end of language learning, but they can make a

real difference to how language flows and to how listeners/readers are able to

process a sentence. Imagine you read “They fell out with …”, you expect what

follows to be a person, not an issue and if it isn’t, you hesitate, maybe

reread, wonder if you’ve understood correctly.

Word order:

All of the above categories apply to almost any type of

word, but this last issue is uniquely phrasal-verby. ELT materials commonly

teach about the difference between separable and inseparable phrasal verbs, often

in a one-off section, but once students have grasped the concept, they need to

know how it applies to specific PVs they come across. Does the object always

appear between the verb and the particle or always after the particle? If both

are possible, is there a tendency one way or the other? Can a PV only be split

by a pronoun or are there other pronoun-like words that can go in-between, like

everyone, things, etc.?

As you can see, I had hours of nerdy fun researching all

this stuff which I then tried to cram into a few short pages. I just hope that

students get out at least some of what went in!

More about the book here.

Labels: corpus research, phrasal verbs, Work on your phrasal verbs